Last year, my long-time friend and collaborator Dominique Cheminais and I curated GIRLS GIRLS GIRLS, a pop-up exhibition loosely around femininity and its discontents. As I embarked on a curatorial residency at Lemkus Gallery, during which time I would work towards a GIRLS sequel, I was presented with the opportunity to think more deeply about this question: what is it that makes us girls? Who’s us? What’s girls?

Like Jacqueline Rose, I think that “anatomy is a sham,” so when I say girls I don’t refer to biology. Indeed, I’m suspicious of identity and its tentacular associations (gender, sexuality), games of category that are, in my view, too unstable, too in flux, to be pinned down in a word like girls. The way I see it, girls is a mystery. An enigma. A vanishing point. A sense. A sense of bloat and a sense of depletion. A sense, simultaneously, of excess and lack. A sense of being too much—too much and yet never enough. The artists gathered here approach their work from different vantage points, but each shares—in some way, shape, or form—an affinity with this paradox: TOO MUCH, NEVER ENOUGH.

The exhibition is divided roughly into seven parts. I like to think of each part as an occasion. An occasion at which a sense of girls becomes palpable. The occasions are as follows: THE WOMB, THE MODEL, THE MIRROR, THE TOUCH, THE MONSTER, THE GODDESS, and finally THE GIRLS.

THE WOMB

We begin as girls. All of us. Yes, even you! In the womb, the bounds between gestator and gestatee are dubious. That is to say, in the womb, we are partly ourselves, partly our mothers. When we are embryonic, we are, at best, blobs and, at worst, parasites. Gabriele Jacobs’ and Yolanda Mazwana’s paintings reflect this transient state between flesh, blood, and water-–the fetal becoming that depends upon the maternal unraveling. This fluidity, which presupposes metamorphosis, haunts us for the rest of our lives, representing, as it does, a state of oneness to which we long to return and yet find inexplicably terrifying. Traces of this terror can be found in legends upon legends of mutation, in which a human being (often, notably, a girl) is transformed into an amphibious or otherwise bestial creature. Jacobs’ and Miró van der Vloed’s sculptures embody this chimeric quality. Jacobs’ aptly named Chimera sees three ceramic heads emerge from a sheepskin body, while van der Vloed’s Skattebol and Naeltjie—made with felt and porcelain glazed with iron oxide—simultaneously comfort and repulse with their soft fur and pert teets. This is what mothers do, psychically speaking, what girls do, what we all do: comfort and repulse.

THE MODEL

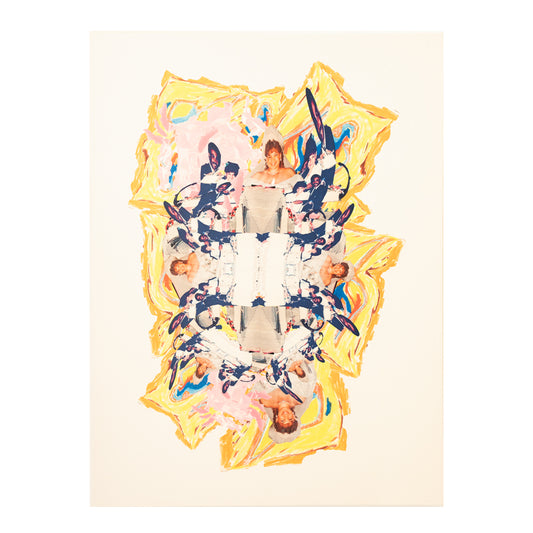

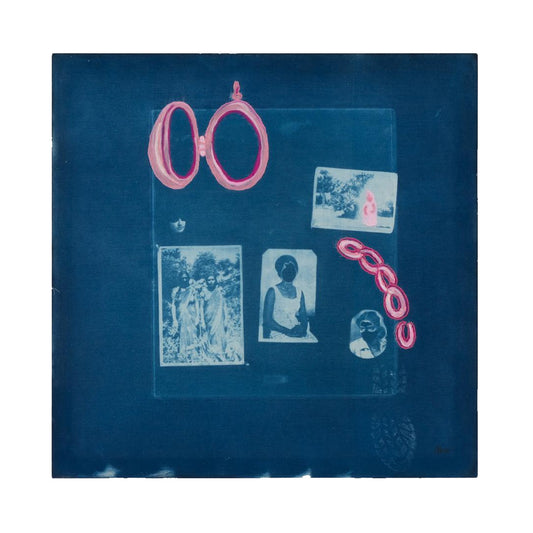

One is not born girl, but rather becomes girl (to paraphrase Simone de Beauvoir). By girl, in this case, I mean the arbitrarily gendered attributes and affectations that our culture associates with girlhood: dresses may come immediately to mind, or trinkets in every available shade of pink. Regardless of sex assigned or gender adopted, we all learn the terms of girlhood from models. The model takes, predominantly, two forms. Mothers, grandmothers, aunties and the like are models. When we were children, we took note of their clothes, their cooking; we noticed, consciously or unconsciously, the subtle discrepancies between the language they used with each other and the language they used with men. When we became interested in performances of femininity, it was to their signifiers that we turned: we clumsily slathered on their lipstick or waddled around in their shoes. Alka Dass’ and Queezy Babaz’s works make use of a combination of family photographs, queer archives, and self-portraits to convey how the images of these models, whether they be blood or chosen family, churn through the tiller of our imagination and thereby come to influence aspects of our own femininity. The second form of the model is the pop culture icon: the girls we saw in movies, and magazines, on the Internet and TV, who gave rise to much desire and aspiration. Nano Le Face’s drawings on paper depict archetypes of this media-mediated femininity: models, tennis stars, muses. We cannot help but feel a mixture of titillation and alienation when confronted with these images because they present a fantasised ideal of girlhood (notably, in the bulk of Le Face’s work, white girlhood) that remains forevermore out of reach.

THE MIRROR

“In solitary pleasure,” writes de Beauvoir, “it may happen that the woman splits into a male subject and a female object.” John Berger echoes this sentiment: “The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object—and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.” The mirror is where this aspect of girls is most lucidly contained: it is an object that contains the image of the observer—we might even say that it is the site where the observer becomes object—and therefore becomes the target of all manner of projections, from illusion to insecurity. Tyra Naidoo’s Untitled works see figures who contemplate themselves in mirrors, mirrors that reflect a fantasy, or perhaps a more palatable, image. Cara Biederman’s John Berger if He Was a Girl similarly depicts a figure who contemplates herself as she paints a self-portrait, while a male model poses pointlessly, as if his very presence demands the artist to turn her gaze to herself, to render herself sight. Kerry Lee Chambers’ sculpture sees a peculiar form, cast from pantyhose, suspended from the ceiling on a long woolen string; a mirror, balanced on a block of soapstone, peers into its orifice, revealing the voyeuristic aspect of the mirror, the libidinally-charged pleasure-shame of looking. As if to cathartically expunge the anxiety that arises amidst all this looking and being-looked-at, Naidoo’s Bacchae-coded Untitled III shows a bloodbath which, suggested by the nude figure’s conspiratorial pose, enacts a sort of vengeance on her onlookers.

THE TOUCH

If we are going to talk about girls, we’d be remiss not to confront the violence to which they are all-too-often subjected. Psychic, symbolic, and physical violence are so terribly entangled in the fabric of patriarchal society—to the point that, in 2020, the government of South Africa declared gender-based violence a “national emergency.” The very term, gender-based violence, is an abstraction of the more disconcerting reality of the touch. That is—for many women and girls as well as queer and gender-non-conforming folk—the same hand that delivers a caress could just as easily execute a blow. This is the atmosphere into which Sara Matthews’ student film, sorry for what i made you do to me, enters. In it, the artist has asked her classmates to punch (or slap) her in the face. The puncher, moreover, must sign a contract that stipulates their consent to be filmed and interviewed before and after the punch. They must furthermore “solemnly vow to refrain from apologising in any capacity, whether directly, indirectly, verbally, non-verbally, visually or through written communication, both before the act or at any point in time in [their] relationship with the punchee post-punch.” The resulting videos are staggeringly complex and borderline controversial—intentionally so. The usual dynamic is turned on his head, whereby Matthews (the punchee) assumes the role of instigator, the controller, the force—in her reflections she describes the process as “exhilarating”—while the participants (the punchers) become flustered, ashamed, and anxious about the moral dubiousness of their actions. At the same time, a video that Matthews recorded after a session with her therapist sees her reflecting on the fact that, while the performance disavows the usual dynamics at play in the punch, the violence she inflicts upon herself could, nevertheless, reveal a lack of regard for her own body. It would seem that power—and how one wields it in relation to oneself—is as slippery as it is hazardous.

THE MONSTER

Girls, in their excess, are considered monsters. In the ancient world they were sirens and witches; in more modern parlance we’d use terms like femme fatale, man-eater, gold-digger, baddie. Whatever the moniker, the effect is the same: girls become monsters when, to quote Rose, “desire lights upon its object, finds itself disarmed and then punishes the woman for the upset produced.” Lebogang Mabusela’s Johannesburg Words Vol. 3 depicts this occurrence at its most vulgar: the catcall. The propositions (“Just a coffee date luv”), flirtations (“Una ke batla wena”), and insults (“Hello makoti”) to which women (particularly Black women) are subjected on a regular basis reveal just how entrenched in the collective psyche is the desirer’s tendency to externalise his anxiety by blaming it on the desired. Kerry Lee Chambers’ Big Red illustrates a similar conundrum. The sculpture, wrapped in red book vinyl, looks like a talon. The tip of the sculpture seems, at first glance, to be prettily poised, like a ballerina’s pointe, but in fact, it is pinned—nailed down by an old worn tent peg. The implication is that to be poised is to be pinned—to be made (or to make oneself) Other in the face of desire, to walk the thin line between erotic mystery and monstrousness. Charity Vilakazi’s paintings on paper and Dominique Cheminais’ paintings on canvas, on the other hand, delight in the idea of girls as monsters. Their figures are largely nude, which presumes that they are on display in some way, and yet their playful and sometimes grotesque long-limbedness, their serpentine forms, are ungraspable and, therefore, sort of sexless. They give rise not to desire-panic, but plain bewilderment.

THE GODDESS

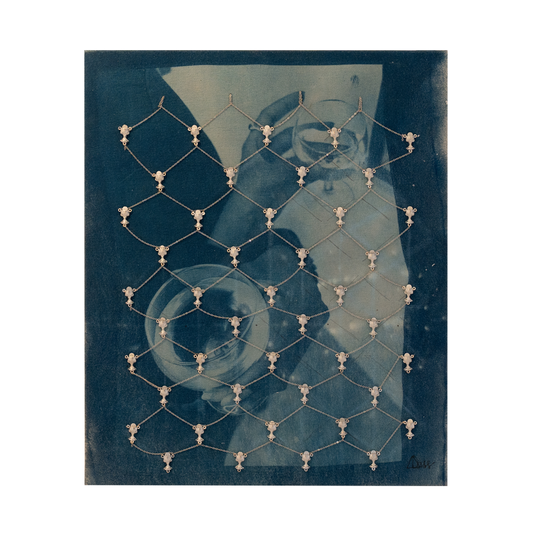

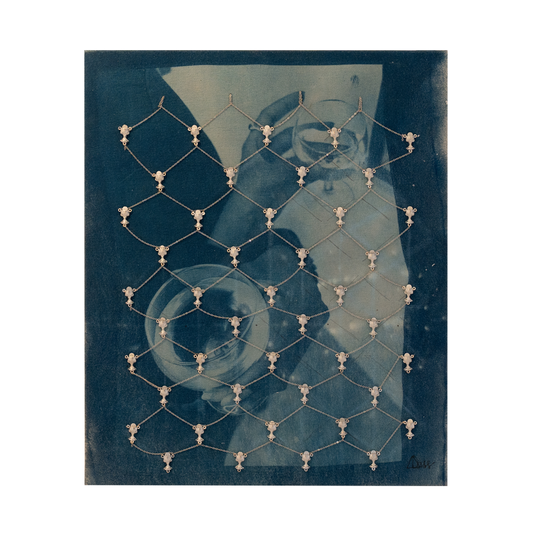

The inverse of the monster is, of course, the goddess. Just as the desirer may project his insecurities onto the desired, he may also invest in her all his hopes and dreams. She is vaulted, heralded, a privileged object. It is as if, through her quasi-divine presence, the desirer will be ameliorated, he will find himself, he will be exalted. There are various ways in which we all play into this fantasy of the transcendent self—from beauty and wellness regimes to performances of self-aggrandisement—and we are never sure where on the spectrum between empowerment and delusion these acts befall. Neha Misra’s and Leah “Lux” Mascher’s works wrestle with this confusion. Misra’s Dream Girls combines cosmetics and plastics to represent the tensions embedded within ideals of femininity, the sense of being commodified and yet unwanted, used and then discarded. Mascher’s Desire Script and Pinch are two photographic self-portraits that appropriate religious imagery—sacred heart, votive candle, gothic script—in the service of seduction. They are nudes—or are posed as such, complete with Playboy-style faux-fur carpet—that highlight how feminine iconography is fetishised, the visual throughlines between lustful Aphrodite and the pious Virgin Mary.

THE GIRLS

The exhibition’s main space—featuring works by Cara Biedermann, Sichumile Adam, Jet Snaith, Lebogang Mabusela, and Nabeeha Mohammed—brings us back to the beginning, to the paradox: too much, never enough. The figures in these works are feminine, but feminine insofar as they have passed through the meat grinder of perceiving and being perceived. The feminine body, if it can even be pinned down long enough to be defined, emerges as a glimpse, a hunch, a suture, a shudder, a myth, a monstrosity. Beauty and ugliness, elegance and trash, sacredness and profanity, pride and self-deprecation—these are just some of the contradictions in which these works traffic. Contradictions that, alone, might produce a sense of unease but, together, form what I can only describe as a motley band of misfits, a fabulous array of bodies in all their glorious embellishments and, equally, in all their shame-ridden shortcomings—in short, THE GIRLS.

Sold out

Sold out