Yolanda Li is a budding contemporary artist who recently graduated from the Michaelis School of Fine Art. Her graduate project, Blue Sky Green Grass (2024), was hyper focused on a single image: Charles O’Rear’s Bliss (1996) — now synonymous with Microsoft’s Windows XP operating system. So far, Li’s practice could be characterised by its preoccupation with representation, specifically the ways in which aesthetic traditions trace out and impact human experiences. These concerns manifested mainly through performative video work, revealing a sensitive reflection on the afterlife of images in the digital realm.

Having had time to reflect on the conceptual basis of her previous work, which looked at the pervasiveness of simulacra [1]. Li began considering the broader implications of sublime imagery, including its psychic dimension and perpetual proliferation in art and mass media. Notions of the sublime are codified in 18th-century philosophy and describe a set of reactions to powerful visual stimuli, i.e. views of the natural world that arrest the senses, inspiring strong emotions like fear and awe. Burke (1757) believed that sublimity was the most profound emotional effect that art could elicit, while Kant (1790) further insisted that the sublime revealed the tension between reason and sensory experience.

In part due to its establishment in structuring models for thought, and because of its canonisation in seminal works of art [2] and literature [3], the notion of the sublime has been extrapolated ad nauseum in contemporary discourse, to the extent that confuses its coherence as a definable concept. Not only that, the presence of sublime imagery is highly predictable, reappearing cyclically during times of rapid environmental and economic change For instance, the trope of ‘terrible nature’ is imbricated with anxieties about capitalism; weather and the global market are similarly volatile. For Li, it is precisely this overabundance and overuse of sublimity that warrants further consideration and begs the question: what function does its saturation in contemporary culture serve?

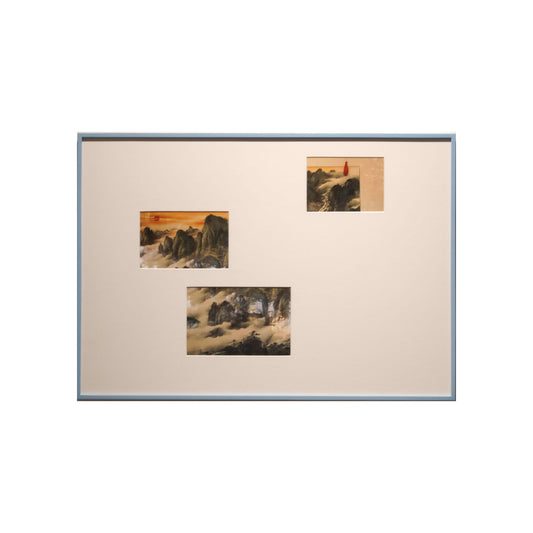

The included works respond to this question by demonstrating the relation between sense and symbolism; the ways in which images act as a mechanism for social control, emotional manipulation, and reinforce cultural values. To this end, Li borrows practical and stylistic conventions of retail-oriented marketing, at times co-opting its infrastructures for production. As a metacommentary on how images become standardised through capital, Li actively homogenises disparate sublime fragments through filtration: an image of an image of a landscape painting, a slinky made from interwoven stills of a video performance, a cloudscape of a cloud atlas, superimpositions of self-translated poetry and several other process-based speculations.

The exhibition title, Turning and Turning, borrowed from William Butler Yeats’ The Second Coming (1920), references an idea of the world that is grounded by the sublime—a simultaneous holding of awe and threat. Accordingly, Li’s work explores the similar ways in which sublime images capture and coerce us, shaping our connection to society, nation, and the environment.

[1] Simulacrum broadly refers to an image or representation of something, but more specifically captures the idea of an unsatisfactory copy or substitute for something ‘real’.

[2] Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818); J.M.W Turner, The Slave Ship (1840); Kazimir Malevich, The Black Square (1915); Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991).

[3] Cassius Longinus, On the Sublime (213–273 AD); John Milton, Paradise Lost (1667); William Butler Yeats, The Second Coming (1919); Karl Marx, Das Kapital (1867).