Lemkus Gallery presents Spes Bona, a solo exhibition by Kamva Matuis. Originally from Burgersdorp in the Eastern Cape, Kamva Matuis (b. 2002) is an emerging artist and student at the Wits School of Art with a rare aptitude for figurative painting. Presented by Jared Leite, the exhibition marks the artist’s commercial debut in the city of Cape Town, and the second individual project hosted by Lemkus Gallery independent from the residency28 programme. Our collaboration with Matuis came to be through an ongoing exchange about his practice, shared research interests, and a mutual appreciation for the medium and history of painting in South Africa.

Despite his young age, Matuis’ education and life experience to date have formed in his burgeoning practice an impressive thematic range and representational ambit. His lens could be characterised by introspection and a particular attentiveness to the world—the social atmosphere and metaphysical paradigm of post-apartheid South Africa. Matuis draws inspiration from key moments, places, and figures of social and political history, but in ways that evoke an overarching sense of pessimism. His work, which during the earlier years of his study was preoccupied with notions of death, has since been engrossed with ‘hangovers’: remnants of slavery and colonialism in pastoral communities, urban architecture, monuments, spatial planning, cultural practices, pedagogy, and perception.

Considering the function of painting for Matuis as a way of grappling with weighty subjects, the exhibition title ‘Spes Bona’, is intentionally a misnomer. Latin for ‘good hope’, the phrase is primarily tied to the Western Cape, and describes the function of Cape Town to facilitate the economies of Dutch and British colonialism. From an Afro-Pessimist perspective, one might argue that the ‘hope’ in ‘good hope’ came at the cost of social death— the symbolic currency of subjection. Appropriating ‘Spes Bona’ within the context of Matius’ painterly reckonings, elucidates the fragility of a society built on a false promise, one that it continues to suffer from.

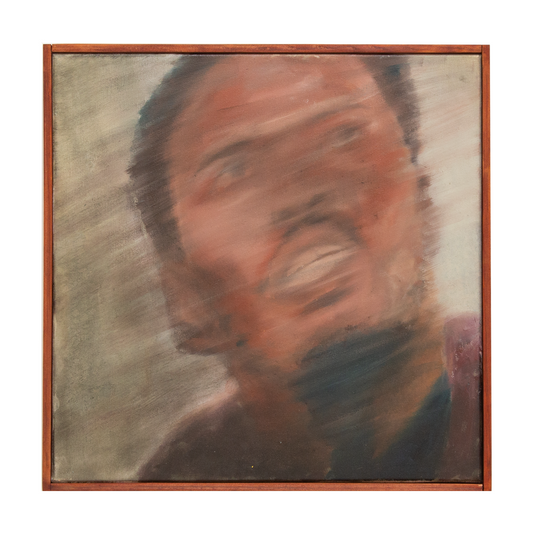

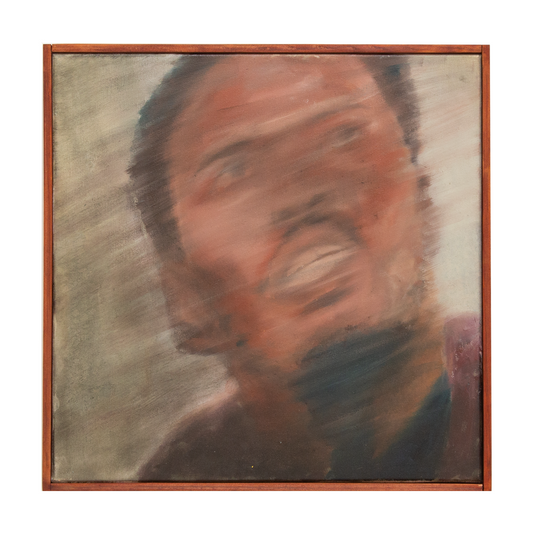

Although the exhibition title references the history of Cape Town, the works span multiple places and points in time. Blurry portraits of Steve Biko and Dumile Feni loom amongst living subjects. Studies of statues: the first Taal Monument in Burgersdorp, the statue of Cecil John Rhodes (covered in plastic) at the University of Cape Town. Miniature flags, relics of apartheid’s Bantustans (Ciskei, Transkei). A painting of the artist’s family home.

A broad range of symbols are included in the works. Oranges littered throughout the foreground of larger works allude to rural life but also the allure of sweetness: a sensory override of ongoing social woes. An old pink blanket, not traditional but with a familiar floral pattern, moves from one work to another. Old brown furniture, ornate plates, brassware (hand-me-downs from the farm owner’s home) stand in stark contrast to bodies and body parts (both human and animal). Totems, consisting of animal bones accumulated over time, function as a record of rituals commemorating cycles of life and death. Together, these elements reveal the different vantage points from which Matuis converses with past and present.

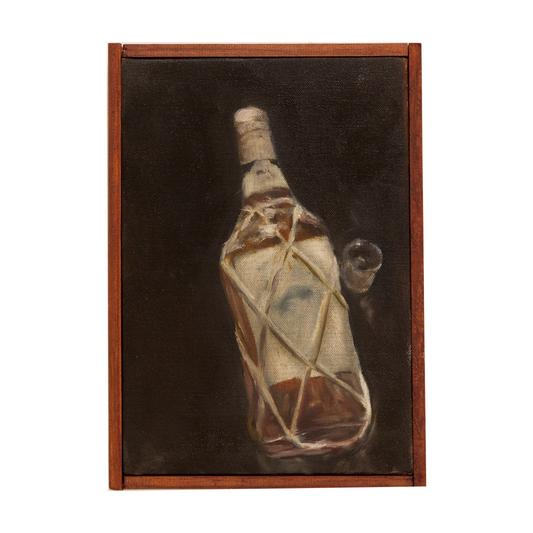

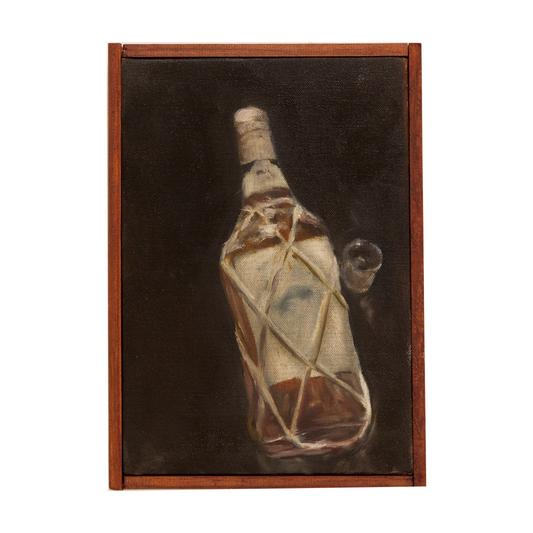

Hailing from the small and dusty town of Burgersdorp, the site on which the Afrikaner Bond was formed in the early 20th century, Matuis laments about the difficulty of constructing an identity around such a place. “It’s hard to feel sense of pride about where I’m from, mainly because we don’t own shit there.” His sentiment reflects the tension between Xhosa culture and Dutch extraction, the consequences and cataclysms that stem from their strained relation. Antagonism echoes even in the enactment of cultural traditions. Colonial dispossession abstracts cosmological constructs. Identity becomes fragile, fighting to sustain itself, struggling to assert or ascertain its own image. In lieu of a stable identity, then, Matuis paints around Blackness: light blue exterior paint (typical of homes in the Eastern Cape) as the underpainting, grape vines, a bottle of brandy at the doorway, a cross-section of a cow’s lung.

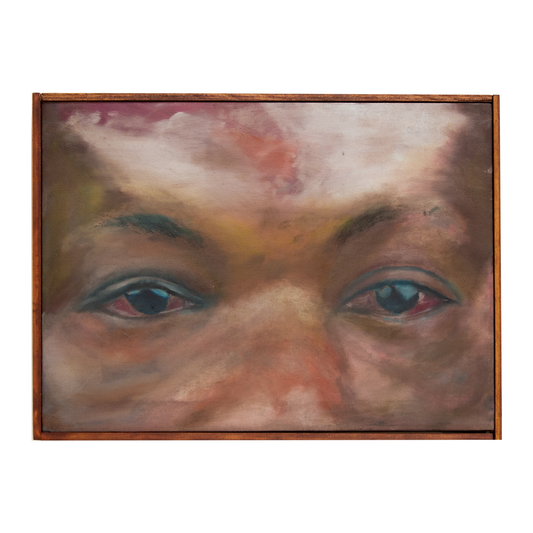

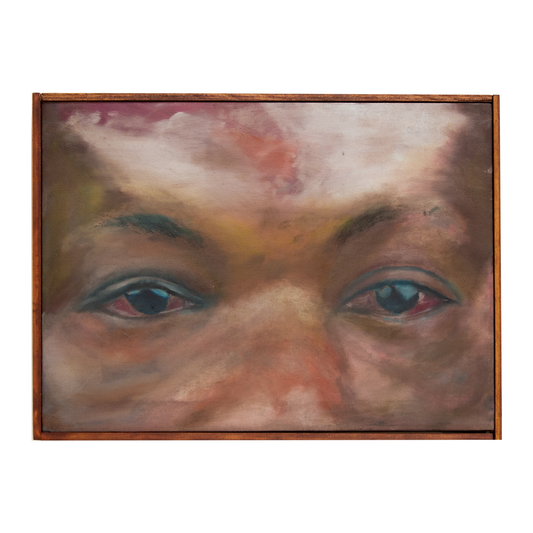

A key series of works feature closely cropped compositions of eyes: a nuanced interrogation of the cliché, ’eyes are the window to the soul’. What then, do tired, scared, bloodshot eyes, imply about the image of the one’s soul? How does appearance, subject to the gaze, inflect inner being? These closely observed ocular anomalies (redness, glossiness, dilated pupils) also index legacies of intoxication, labour coercion, state induced drug dependencies, the lasting effects of the dop system (especially in farming communities). In the not-so-recent past, eyes were marker of race: a means to point out, or pull away, one body from another. Notwithstanding the delicacy and empathy in the execution of these portraits, Matuis’ pieces are imbricated with more sinister ways of seeing.

Though this body of work could be considered a treatise on the notion of hope in post-apartheid South Africa, one that takes seriously the afterlives of slavery and apartheid in present day and leaves little room for optimism; a glimmer of possibility pervades. This is the great contradiction of Matuis’ latest offering, that in defiance of his own cynicism and staunch political critique— the works invite hope. Hope for a shift (or perhaps a return) in the trajectory of Black figuration. Hope in the practice of painting, not only to portray, but to grapple with something, to utter the unutterable, to pose troublesome questions. As a debut exhibition, Spes Bona encourages a conversation around the irreconcilable burden of hope, the bearing of an incompatible responsibility, and the arduous work of representation.

Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out Sold out

Sold out